The sun shone on Lewiston as I made an early start for the long drive to Portland. I would spend the day bouncing between Washington and Oregon – the Columbia River is the border between the two.

The plan was to avoid the interstate as much as possible, and the first stop was Sacajawea State Park in Washington. Sacagawea (the spelling of her name is still a bone of contention see here) had nothing particularly to do with this area, but was adopted by the American suffragette movement as an example of a strong female figure (and arguably the first woman to be given a vote in the United States, as we shall see in a couple of days time), and this park was established by them.

Chicago may be the windy city, but Washington was doing its best to be the windy state. The never-ending green hills of the Dakotas and eastern/central Montana and the forested mountains of the Rockies were replaced by exposed brown windswept slopes. The car was fighting the crosswinds as I headed for Pasco.

The road doesn’t follow the river that closely, and I didn’t meet up with it again until the park, which sits at the confluence of the Snake and the Columbia. This critical junction meant that the spot had long been a centre of trade between tribes. Sadly, the actual point of the confluence was closed off for research purposes, but you can get down to the shore of both rivers. The Corps reached the confluence on October 16, 1805 and were greeted by some 200 Indians singing and dancing.

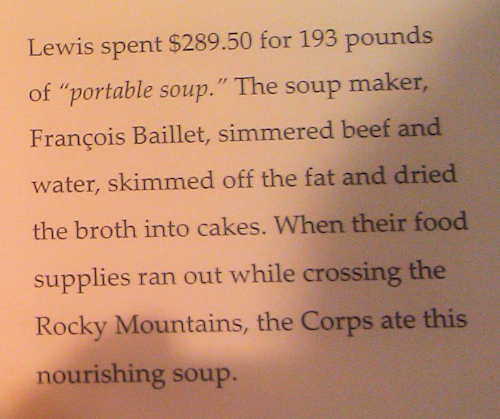

The museum was rather good – much of the usual stuff of course, but a few new factoids for L&C fans, including a recipe for the dreaded portable soup.

There was also an examination of the importance of the salmon to the Indians of the Columbia river. The salmon has a similarly spiritual significance to these peoples as the buffalo did for the Plains Indians.

Having expressed my L&C interest, Rebecca, the “interpretive specialist” on duty, took me backstage to show me some paintings from the 1940s depicting local Indians. They were initially on display in the museum but were deemed “obscene” (there was a lot of nudity) and were taken down. They now hang in the park office, and are clearly only for those of us deemed mature enough to cope! What the trustees would have made of Picasso I dread to think. She also showed me a copy of a map that overlaid the current river banks at the confluence with how they would have been in Lewis & Clark’s day. They weren’t actaully so different.

From the park, I followed the Columbia Gorge to the oddly named town of The Dalles (ryhmes with gals). The gorge is a fairly rare geological phenomenon, created through a combination of volcanic activity and fluvial erosion. The basalt strata are clearly visible, although if proof were needed of the impact of volcanoes in this part of the world, the looming presence of Mt Hood, rising 11,000 feet to a perfect cone and covered in snow is more than sufficient.

Mt Hood was not named by Lewis & Clark. It had already been mapped by George Vancouver in the 1790s as part of his exploration of the northwest coast. In other words, the Corps of Discovery was back on the map.

The Dalles hosts the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center (not to be confused with the Columbia Gorge Interepretive Center a few miles further on). There was some Lewis & Clark stuff here, but it wasn’t the best for expedition fans, and actually the local museum that was also housed there was more interesting.

By this time the Corps was rocketing down the Columbia, taking risks with rapids that they would not have done had they not been conscious of the impending arrival of winter. They did have to have some portage sections, notably around Celilo Falls. These impressive waterfalls no longer exist, having been wiped out after the dam at The Dalles was constructed. This still rankles with local Indians, for whom the falls were an ancient fishing ground – there are plenty of photos of precarious looking wooden platforms jutting out over the boiling waters, with rods dangling from them to catch the salmon.

The landscape then changed rapidly from the arid windswept hills of the gorge (I actually passed trucks transporting the gigantic blades for wind turbines – they are impossibly large, like thin wing sections of intercontinental airliners) to the forested slopes that one associates more with the Pacific Northwest. Scrubland becomes pine forest and dappled sunlight replaces blazing open spaces.

My final stop of the day before deviating away from the Columbia was Beacon Rock State Park. Beacon Rock is a towering outcrop that stands like a sentinel on the nothern bank of the river. Clark originally refers to it as “Beaten Rock”, but later changes this to Beacon Rock, which seems more appropriate.

As well as offering a wonderful view to those fit enough to stagger up the 100 year-old trail that winds round the side of the rock, Beacon Rock is also approximately marks the spot where the Columbia becomes a tidal river. It’s still a long way to the ocean from here, but nevertheless, there is a low and high tide mark, and the captains remarked on this.

![]()

Inevitably, early on a Friday evening, the traffic was heaving coming out of Portland and, compared to what I’d been driving in since leaving Missouri, pretty heavy everywhere. With the sun in my eyes, I relied on my trusty GPS to spit me off the expressway and into the squeaky-tight car park of my hotel on the edge of downtown. After three weeks away from urban pleasures, I was going to have a Saturday in one of America’s most livable cities.