You might think that having negotiated the rapids of the Columbia and reached calmer waters of the lower river that the Corps would find the final leg of the expedition plain sailing. This was not the case. The Columbia in fact is so wide at its estuary that the captains mistook it for the ocean itself near what is now Skamokawa Park. Clark was moved to write “Ocian in view. O! The joy!”.

This far west, the Columbia certainly has weather conditions unlike anything the Missouri had thrown at them. With winter approaching, storms became a problem and their riverine canoes were not well-made enough, or even the right design, to cope with such waters.

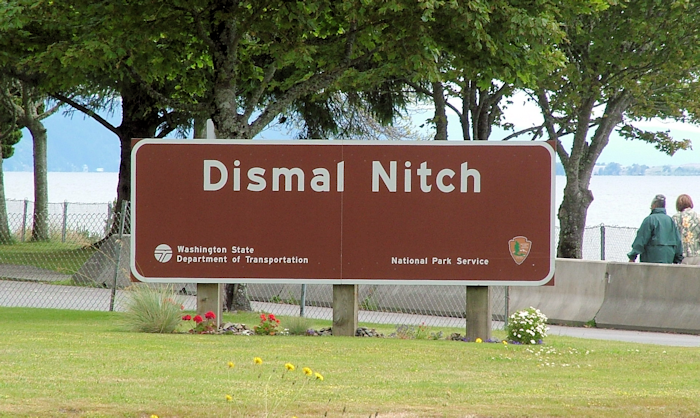

In fact, despite the elation at having made it to the coast, the time spent by the “big water” was one of the least pleasurable of the entire trip. It started badly at a place Clark referred to as “this dismal nitch”, a name that lives on today.

The Corps found themselves holed up here for six days – kept at bay by a violent storm and with only just enough space for them all to camp above the high tide mark. I was kept at bay by a coach party – the first one I’d run into.

The local Indian tribe, the Cathlamet. paddled over (in their much more suitably designed sea-faring canoes) to sell them some salmon. The locals around these parts were very familiar with white men – they had been coming in tall ships to trade for many years – but none had ever come from the east, or in canoes.

From the Dismal Nitch, the Corps moved on to what became Station Camp where it set up its first base from which to reconnoitre the surrounding area.

Lewis & Clark separately headed off overland on the north shore of the Columbia to investigate. They explored Cape Disappointment (named by an English explorer who’d failed to find the mouth of the Columbia), and bartered with the local tribe. The Corps was pretty much all out of trade goods by this stage, so needed some bargains, but these Indians – well-versed in trading strategies with both each other and the white men from the tall ships – were no pushovers. Deals frequently collapsed as the Indians demanded what the captains deemed too high a price.

In fact, the Corps never struck the same friendships with the coastal Indians that they had with those back east – the journals regularly refer to acts of petty theft from native people. Add to this a few misunderstandings, and things got a bit tetchy at times, with the Corps ultimately stealing a canoe that they couldn’t agree a price for but then striking a deal after the effect. Given that Lewis & Clark’s code of honour is never questioned, this crime suggests how aggrieved they must have felt.

Perhaps all this hard dealing explains why the woman at the cash desk looked at me blankly when I quipped that perhaps the admission price to the L&C Visitor Center should be waived for someone who’d just completed the entire trail.

The visitor center is good but not great. Naturally I was most interested in the facts pertaining to L&C’s stay on the coast and skipped through all the “Jefferson had a vision” material. They did have a few actual objects from the trip courtesy of Sergeant Patrick Gass’s family (remember him? He was the one elected to sergeant after the sad death of Charles Floyd back in Iowa).

The ocean was fairly calm and from the vantage point of the North Head Beach lighthouse it’s possible to see that the Columbia river channel extends a few miles into the ocean, which is incredibly shallow here (thus the need for lighthouses – the Columbia Bar, a sandy area just submerged during high tide, is also a major hazard for shipping, which is why this whole area is known as the graveyard of the Pacific (I don’t think it’s the only place claiming that title!)).

I explored the park, visiting the log-strewn Waikiki Beach, Mackenzie Head, which Clark explicitly refers to, and generally pottering about taking pictures of nothing but sea.

I then drove up through the tourist centre of Long Beach – which is really a collection of strung-out towns. From the road it’s not the most appealing of places and I was very glad that I wasn’t staying in one of the umpteen motels along the strip.

Further out along the peninsula I took one of the many side roads to the beach. These roads have perhaps five or six houses either side and do literally lead onto the beach. Some stretches of the beach are driveable, but I thought I’d put the car through enough so just parked it near the ocean for its photo-op.

The fishing port and harbour of Ilwaco (rhymes with Darko) was far more appealing than the gaudy t-shirt shops of Long Beach. I settled into my “Portside Room” at the Harbour Inn and then had dinner at the aspirational Pelicano restaurant overlooking the harbour itself.

After one of the best night’s sleeps I’ve had since setting out (no-one mention the sea air), I chatted with the excessively well-travelled Janis – the innkeeper – over breakfast as I was the only guest before heading across the Columbia from Washington back into Oregon.

From their base at Station Camp, and knowing that they were destined to spend the winter on the coast, the captains took the unusual decision of asking the Corps, including York (Clark’s slave) and Sacagawea, where they thought they should build their camp. There were several options but the winner (and the captains’ own preference) was on the south shore of the river near the Clatsop tribe. Elk were plentiful there, ensuring a good food supply and there was better ground.

Fort Clatsop has been recreated, much like Fort Mandan, although this time the location is more accurate but the layout of the fort is more or less guesswork as there are no records. It has been done in much the same way as Mandan in fact with more spacious quarters perhaps, but less room in the yard.

It must have seemed more like a prison than a garrison that winter. The weather was atrocious: over several months there was just a handful of days when it did not rain, which is unusual even in this rainforest climate. Their clothes were rotting and they weren’t enjoying the same sort of hospitality bestowed on them by the Mandan tribe the previous winter.

No sooner did they arrive than the men began preparations for their departure. They might have reached the Pacific, but they still had to get back to St Louis and report back to Jefferson. The men mended clothes, tanned hides, kept up guard duty and – further down the coast – boiled gallon upon gallon of sea water to extract salt with which they could preserve meat for the winter and the trip back.

The visitor center was ok, although the video was told – rather patronisingly I thought – from the perspective of the Clatsop tribe and was actually quite annoying. One of the rangers (or interpreters as they like to call themselves) told me that the next talk was at 11.30 and was called “Amazing”. And what’s it about, I enquired. “I don’t know, I just know the ranger giving it and it will be amazing”. Hmm. I didn’t go, but as I was wandering round the fort it was unavoidable as it was amazingly loud – it was in fact a few facts about the expedition, which I was already familiar with. But of course for many people this is their only exposure to the world of the Corps of Discovery so of course they should be told how amazing it was – just perhaps ever so slightly more quietly.

It is possible to walk from the fort to the coast, but by now it was appropriately raining harder and harder and a 6.5 mile hike through damp forest wasn’t winning me over. So, much like Lewis, I left Fort Clatsop earlier than intended. The Corps eventually left in late March having finally had enough of the climate, the people and the confinement.

I drove south to the imaginatively named town of Seaside, which turned out to be a fairly ghastly tourist resort. There was a statue of Lewis & Clark overlooking the beach. They looked a bit pissed off too and a bird had shat unceremoniously on Lewis’s hat. I didn’t feel it was right to take a photo so instead you can see what they look out at.

The salt works was supposed to be around here, but the traffic, rain and lack of clear directions meant that I kept going to the final stop on the coast – Cannon Beach and Ecola State Park. This is a really lovely park with lots of hiking opportunities that I didn’t partake of and some fantastic views.

The ocean was a bit rougher today although still far from stormy, but it lent the beaches a misty Pacific Northwest atmosphere that I love, but wouldn’t want to camp in for four months.

It was near here that a whale washed up during the Corps’ stay and Clark took a group of men (plus Sacagawea who insisted on coming to see the animal and the ocean) to see what they could salvage from it, but they were too slow and ended up having to trade for blubber and whale oil.

And with that I turned the car east for the first time in more than three weeks. Like Lewis & Clark, I had to make my way back. They were heading back up the Columbia, I was going cross-country to Portland and from there flying to Yellowstone.

The westbound Lewis & Clark trail was done. I had travelled 3,800 miles from Camp Dubois in Illinois to Cape Disappointment in Washington with the Missouri, the Rockies and then the Columbia and its tributaries as constant companions. I hadn’t discovered anything new to science – although I had learned that what Americans call a flapjack isn’t what we call a flapjack. Most of the locals had been friendly, the scenery spectacular at times, and my understanding of the American west greatly enhanced. I’d even written a journal. Thanks for reading it.

You may have to wait a little while for the postscript as Yellowstone isn’t famous for its WiFi. There’s still much to wrap up – how the Corps split into five separate groups yet still arrived together in St Louis, how two Blackfeet Indians were tragically the first and only victims killed at the hands of this military expedition, how they said goodbye to Sacagawea and what happened to Lewis & Clark themselves after returning from a trip few thought anyone could survive.