“The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri River, and such principal streams of it, as, by its course and communication with the water of the Pacific Ocean may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce” Thomas Jefferson’s instructions to Captain Lewis, June 20th, 1803

Lewis & Clark spent the winter of 1803/1804 at Camp Dubois in Illinois, just a few miles north of St Louis – the westernmost large city of the fledgling nation of the United States of America. Despite being just 200 years ago, the precise location of Camp Dubois is unknown. Of course this hasn’t stopped it from being recreated somewhere very near where it probably was.

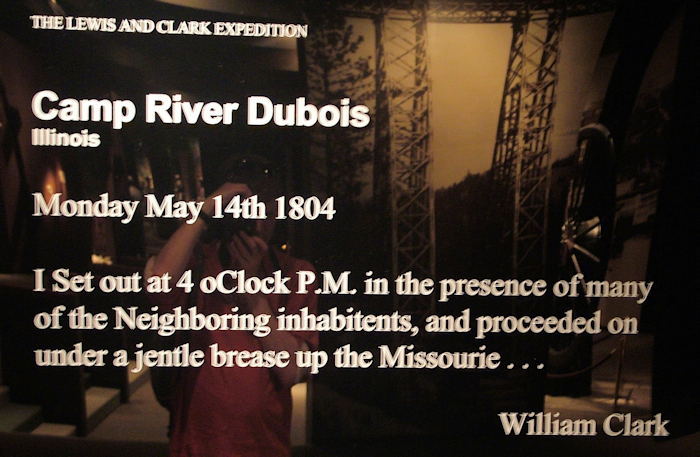

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, together with their Corps of Discovery, set their boats on the Missouri River for the first time on May 14th, 1804. They joined the Missouri at the mouth of Wood River. The reconstruction and nearby levee are slightly to the south of Wood River (ignore what my ill-informed video commentary says!) but no-one appears to mind too much. Cahokia Creek seems to serve just as well to get a sense of those early moments of what was to become a legendary mission of exploration.

My own trip had a less than legendary start. Having dodged the woman conducting a survey on the quality of the breakfast waffles at the Drury Inn, St Louis Airport, I foolishly tried to do the right thing and take the free shuttle bus to the airport, where I could get another free shuttle bus to the Hertz car rental lot. The entire operation took in excess of 30 minutes. I drove past the Drury Inn in both directions no fewer than six times in two different vehicles, only to end up approximately a 10 minute walk away from the hotel. Albeit a walk that wouldn’t have been excessively pleasant with heavy luggage.

Not that this would have stopped Messrs L&C. Their inventory list included two Artificial Horizons, 150lbs of portable soup and 8oz of powdered rhubarb. Not to mention the vast quantities of ammunition and gifts for the Indian tribes they would encounter. I have a couple of T-shirts, a US electrical adapter and a Swiss Army Knife. The big one mind.

As well as not knowing exactly where they wintered, there are also no records of exactly what the boats they travelled in were like. Only relatively recently did some drawings of Clark’s emerge that gave more indication, but even these are not thought to be definitive. A combination of dugout canoes known as pirogues and two keelboats with masts seems to be the consensus. I have a Toyota Camry.

Appropriately, my day began at St Louis’s most famous sight – the Arch. Officially the Jefferson Expansion Memorial Park. You’ve seen it on TV, but it is truly impressive in real life. It’s just so… well, big. And arch-y

Beneath the park sits the Museum of Westward Expansion, which in one fell swoop tells you more about Lewis, Clark, Thomas Jefferson (who’s big in these parts) and the quest to find a water passage to the Pacific than any sane person could want to know. I skim read, and then I looked at the stuffed beaver and the Simpsonsesque animatronic characters. I mocked. Quietly, and unfairly. The museum is free and is actually a tremendous record of how present day continental America came to be. Lewis & Clark naturally sit at the very heart of this story.

Thus it was only fit and proper that I watched the Imax presentation about their trip. And it was good. Not cheesy and rubbish like these things often are. There were no-expense-spared reconstructions of the severe hardships the men endured, there was the acknowledgment that the Indians got a bit screwed by the whole deal despite the fact that by and large tribes were extremely helpful to the expedition, at least those that didn’t try and kill them. There was edifying music. They’d even found an actor for Clark who looked a bit like a young Gene Hunt. “Fire up the pirogue”, he didn’t say. Hell, Jeff Bridges narrated it. What more do you people want!

It was everything you’d expect from a National Geographic film. If I had been lacking courage or conviction, then this film was handing such attributes out like Lib Dem leaflets before an election.

Onwards and quite literally upwards as I clambered into one of the tiny egg-like capsules that whisk you to the very top of the arch. It was busy up there and space is at a premium, as are windows. Thoughts of gazing across the midwest plains with Clark’s cartographical prowess fresh in memory were replaced rapidly by fighting with small children to get the best aerial shot of the baseball stadium far below us.

Camp Dubois was a much quieter affair. The whole story once again – I suspect I shall be able to recite it in my sleep after a month of Lewis & Clark interpretive centres. But a replica of a keelboat and the reconstruction of Camp Dubois itself were worthy exhibits.

As I wandered into camp I was a little surprised to find a child of about 8 playing checkers with a woman who one would assume was his mother if it wasn’t that she was dressed in early 19thC costume and he was… well, he was wearing what most 8-year-old American kids wear – t-shirt, shorts and sneakers. I got a quick rundown of Fort protocol – namely how the guard rota worked, before saying my goodbyes and walking over to a small log cabin across the meadow. Here a teenage girl also in costume did her best to be authentic, but the line between reality and historical reconstruction was getting a bit blurred after a couple of questions from me, so I made my excuses.

Highway 94 – part of the Lewis & Clark trail is a rather spectacular drive that is much better done from the passenger seat. I would imagine. It twists and turns, rises and falls, like the choppy waters of a fast flowing river. It more or less follows the course of the Missouri, which here is so wide that choppy waters are a thing of the past. The road was quiet, allowing me enough glances at the bluffs that flank the river. There are a few towns aloing the route – Defiance is the first of note, and was overrun with bikers (as in Harley Davidson rather than Bradley Wiggins). I took the turning for “Historic Dowtown Augusta”, in dire need of a coffee. This one-horse town turned out to be a gem. Two antique shops (that were probably just one really), and Café Bella, where they said I could have my coffee on the house just because folks round here seem to be like that.

It’s my first foray into the real Midwest and I have to say the cliché of people being properly sincerely friendly is holding true. I had a nice chat with the owner of the antique shop(s), who said my trip sounded so good she wished she could hitch a ride. Frankly, if she can read a map I’m tempted to go back and pick her up. While Clark meticulously mapped the course of the river and all the tributaries and islands, I have a few Google Maps printouts and I still missed the turn for Main St in Jefferson City, the state capital of Missouri. See, I told you Jefferson was a big player around here.

It took the Corps of Discovery 22 days to reach this point. It had taken me about 3 hours. Clark records that they killed some deer that day, which they presumably ate. Food in Jefferson City on a Sunday in June 206 years later isn’t much easier to come by. I ended up in Mike’s Corner Pocket. Not a homoerotic euphemism, but a pool bar whose customers all seemed to either own it or work there. As an homage to my inspirational companions L&C, I too supped on meat. A hamburger. Because they were all out of chicken strips. And catfish strips.

Jefferson City doesn’t actually have much L&C history to shout about, but this didn’t stop the city erecting a whopping great tableau in their honour within spitting distance from the state capitol.

Along with Lewis (in the hat) and Clark (with the sextant), the other Corps members depicted are York, Clark’s slave and George Drouillard who was an interpreter and guide and probably the next most important person behind the Big Two. Notable for her absence is Sacagawea, the Shoshone Indian woman of whom much mythologising has occured. More of her in later blogs!