To do justice to Lewis & Clark’s travels along Wednesday’s leg of the trail would take more time, a much bigger vehicle and – according to one guide book – a saw. From the Bitterroot Valley, they reached Travelers Rest – pretty much the only spot on the trail where there is archaeological evidence of the Corps’ presence.

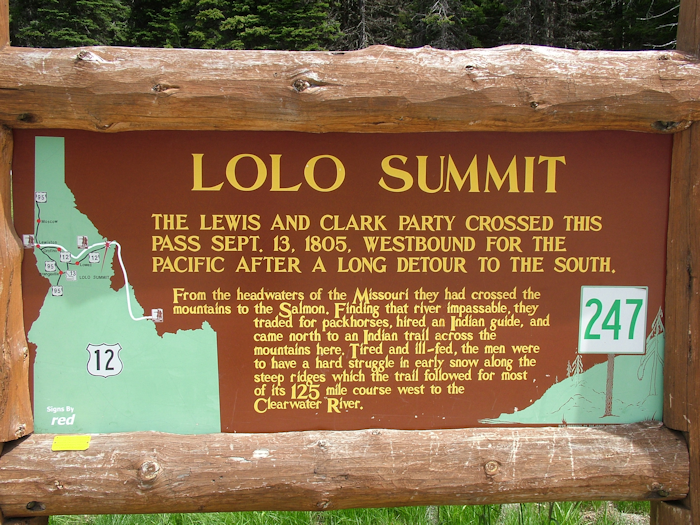

This long-standing crossroads of trade and migration routes was the last stop before the hardest stretch of the entire trail – the Lolo Trail. If the earlier thrashing through the mountains had been tough, they were a walk in a state park compared to the next couple of weeks.

Ascending to the Lolo Pass wasn’t great, but it wasn’t the worse they would endure nor the end of their climbing. The drive up from Travelers Rest is very straightforward – this is no Lemhi Pass road. From the pass you can either look in at the visitor centre, which among other things has a good large relief of the area that shows just how complex and dense the myriad mountain ranges are in these parts.

Or, the intrepid can put the saw in the back of the pick-up, along with the spare petrol and tyres and hit the forest roads, which give you a better indication of the sort of terrain L&C faced as they tried to make their way from the Lolo Pass to a river that would link up with the Columbia. Unlike large stretches of the water route, which have changed through natural and man-made processes, the mountain terrain that the Corps endured hasn’t changed at all. It would still be a brave person who would try and retrace the steps of September 1805.

The Corps had a local Indian guide with them, but he took a wrong turn and they were forced to climb back up a 1,000m mountain they’d just come down. The men were all at their physical limits and were starving. Colt Killed Creek still exists today, and gives one indication of how they stayed alive. Snow came early that September, adding to the misery. That no-one died is astonishing. This was by far the hardest section of the entire trip.

When you come over the top of the pass one of the first signs you see after the “Welcome to Idaho” and “You are in the Pacific Time Zone” signs is one that says “Winding roads for the next 99 miles”. All three signs are accurate. The road – the Lolo Motorway – hugs the river as it drops rapidly from the pass to the valley. Raging whitewater and occasional spells of calm water are a constant companion as the road twists and turns for mile upon mile. Not the ideal trip to take with a cricked neck (another black mark for the hotel in Hamilton).

This early, high section of the Clearwater wasn’t something the Corps attempted, they were still manhandling themselves through desnse woodland on unthinkable gradients. Even in a car it was a tiring way to cover 100 miles and I gladly pulled over at the Wilderness Inn – the first place to stop. It was a classic short-order diner with unlimited coffee and prices geared towards the captive consumer. The woman who owned it had just bought a Kindle from Amazon and was showing it off to a supplier who’d come in to check the order for hamburgers: “Well I’ll be darned – is this what books look like now?”

The road started to flatten out after this point although the river still looked tricky. I took the 11 mile hairpinned detour to Weippe (pronounced We-Ipe) where there was a Discovery Centre.

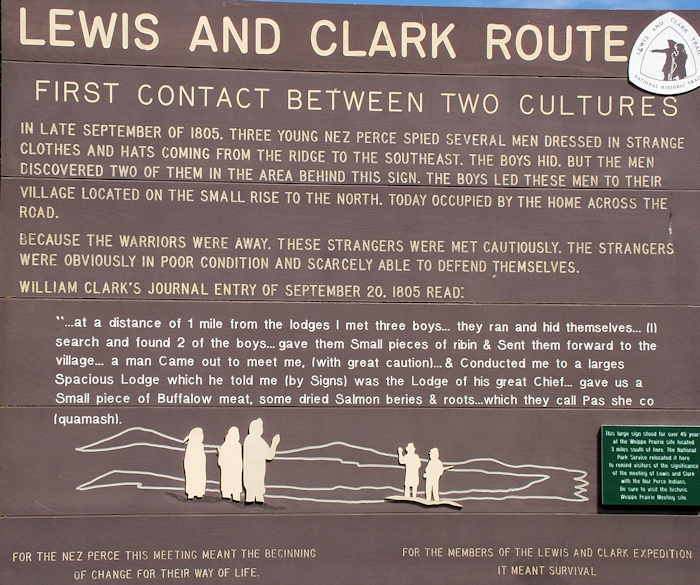

The Corps had decided to split up. Clark took a small group of men in a desperate hunt for food while the others ploughed on. Although clearly a risky strategy, it paid off. Clark and his men stumbled off the mountains and into the high meadows of the Nez Perce tribe at Weippe Prairie.

The groups finally reconvened and tucked into the food the Indians provided. The Nez Perce were suspicious though – the Shoshone were their enemy and this group of white men had this Shoshone woman with them. Normally, Sacagawea’s presence had acted as a sign that the Corps had peaceful intentions, but here it was working against them.

The story goes that the Nez Perce were planning to kill the expedition, but were talked out of it by an old woman who had been treated kindly by white people when she had been making her way back to the tribe having been kidnapped. Another enormous stroke of luck – in their feeble state it’s unlikely the men would have been able to fight off any attack.

From then on, relations with the Nez Perce flourished and the Corps left their horses with the group (one of the few Indian tribes who actively bred horses, and for whom horses were a major status symbol) before creating five dugout canoes and hitting the waters once more – their dry-land ordeal over with for the time being.

The Corps stayed with the Nez Perce for a few days. I didn’t linger so long in Weippe, which is arguably not worth the detour. The Discovery Center in the library does have some Lewis & Clark information, but there’s not much new to be learned here. It’s well off the tourist trail. It was Crafts Day for the kids of Weippe it seemed, although here in this rural backwater’s seat of learning, the kids I saw were more engaged with playing what looked like a multiplayer version of Call of Duty on a gigantic TV screen or surfing the web in the Technology Center.

Back down the hairpins and I was soon skirting along a much wider, calmer and eminently more navigable Clearwater River. The Corps canoed down the Clearwater to the Snake river – at that confluence today sit the twin towns of Lewiston and Clarkston, the former in Idaho and the latter in Washington.

I had two nights in Lewiston, a town flanked by low brown hills. It was an odd place – lots of traffic, an industrial mill town with lots of green corridors, and a seemingly complicated road layout.

My first stop was the Hells Canyon visitor centre where Kristin, who’d been alerted to my impending arrival via Twitter – a sort of 21st century smoke signal -was extremely helpful. Hells Canyon is the name given to a stretch of the Snake River south of Lewiston – it’s a popular day-long boat ride excursion. I trundled out to the Nez Perce Visitor Center, a National Park site, which talks about the Nez Perce culture although barely mentions the Nez Perce Trail, which is a lengthy route into Canada via Yellowstone followed by the tribe as they tried to escape the US Cavalry in 1877 in a conflict over forced removal to reservations.

The local historical museum in Lewiston had the usual slightly overwhelming collection of photographs and documents discussing settlement at the confluence from pre Lewis & Clark to the present day. It also had a collection of Disney character toys. For some reason.

The final stop of the day was the Hells Gate State Park, where there’s a Lewis & Clark centre, that can easily be skipped save for the good 30 minute film about the Corps’ Idaho leg of the journey, which is worth watching.

Also in the park is the Jack O’Connor Center. Kristin had mentioned this, so I thought I go along. O’Connor was a long-time Lewiston resident and a very famous big game hunter. He was a journalist and wrote extensively about his expeditions. The exhibition, which is very well done, is heavily sponsored by various factions of the gun industry and is of course pro-hunting and goes to great lengths to point out the conservation work done by hunting organizations.

Whatever your views about such things – and I certainly struggle to agree with shooting animals for trophies rather than for food – there is no doubt that O’Connor was both a passionate and a decent man. And a bloody good writer judging from the few excerpts of his work on display – not in a macho Hemmingway style but in a considered and authoritiave way. I oddly enjoyed this addition to the day.

And with that, my days in Lewiston and Clarkston were over and, like their namesakes, I would be following the Snake River and reaching the Columbia. The Corps was getting back on the map.