I didn’t linger in Riverdale, I had a few miles to rack up. I was heading to the uninspiring-sounding New Town, largely because the ranger at Trail HQ in Omaha had recommended going to the Three Tribes Museum just the other side. So I did. It was right next to the Four Bears casino. Four Bears was a Mandan chief who was painted in many different guises by artist George Catlin in the first part of the 19th century.

The bridge that connects New Town with Four Bears Village on the Fort Berthold Reservation is quite impressive as bridges across the Missouri go.

The museum was only just worth the detour. The woman behind the desk seemed a bit nonplussed by my request for an admission ticket but the concept finally sank in and she wrote me out a receipt by hand. Fort Berthold is where the Mandan, Hidasta and Arikara tribes settled after being moved from their heartland further downstream by a combination of disease, hardship and forced relocation.

From New Town I declined the opportunity to stop off at the Lewis & Clark State Park, and reached the oil town of Williston. This was a gas and lunch stop and oh dear lord i got a mobile phone signal. The oil fields are booming in these parts and Williston was busy – it felt like a frontier town, a large corporate logo laden version of the wild west. The road from here on was quiet.

After a Lewis & Clark free morning, the next stop was laden with L&C history. A few miles south-west of Williston lies the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. This was a major point for the expedition, who knew that the rivers must meet. You can just see the Yellowstone joining in the middle of the photo.

They got there in late April 1805, and Lewis reports that the oars had ice on them that morning. The wind was against them, but Lewis was sure they were near the confluence so set off on land with a few men to find the junction. The party reported plentiful buffalo, which they duly killed of course, before camping on the banks of the Yellowstone for the night two miles south of the confluence. When he and Clark finally met up at the point where the two rivers meet, “a long wished-for spot”, a dram of rum was offered to all the men.

Obviously I was driving so didn’t partake. I did stop at the excellent vistor centre though, which has two good exhibits – one on general local history and one on the European settlers, specifically those from pre-WWI Germany.

This whole part of the country was largely populated by European immigrants from Germany, Russia and Scandinavia. Indeed Kim, the lovely girl behind the desk, told me she was of Norwegian ancestry, before trying to convince me that the pizza in Fairview (a town that straddles the North Dakota/Montana border) was the best in the US “Or at least the best I’ve had”. She also sold me a detour there to see a vertical railroad lift, which I would have gone to except I got a bit waylaid at Fort Buford down the road.

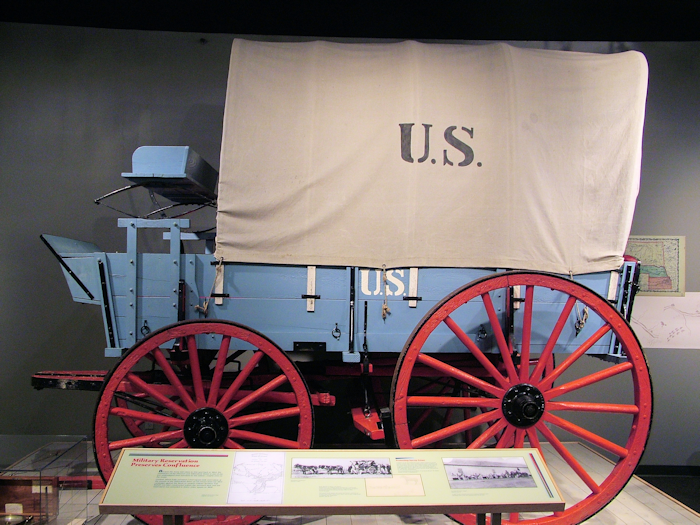

Fort Buford is not a L&C site (although inevitably Clark wrote that it would be a good location for a post). It was a very major military garrison however in the late 19th century and is – most famously – where Sitting Bull finally surrendered. I did find a Lewis & Clark connection though… my enthusiastic guide (or storyteller as there wasn’t a whole heap of guiding to do) was Arch Elwin, who portrayed the Corps’ Sergeant Ordway in all the bicentennial reconstructions a couple of years ago.

Arch regaled me with tales of Lewis & Clark’s return journey. Clark had made camp here and was waiting for Lewis who had taken a completely different route back from the coast. Clark waited a week until the agreed meeting time and then took off, plagued by the sea of flies and bugs that infested the area. He left a note for Lewis. Next on the scene was one of the Corps who had been left behind to hunt, who arrived at the deserted camp, saw the note (which he couldn’t read), took it and caught up with Clark. He arrived with no meat and a note not meant for him. Clark was obviously unimpressed. Lewis was only a couple of days behind, and thankfully realised that Clark had been at the site and moved on and the two were swiftly reunited.

The telling of all these tales, with the enthusiasm of your best history teacher, all took some time and meant that I had to forgo the culinary and locomotive delights of Fairview.

I rejoined Highway 2 and headed into Montana. My destination for the night was the Fort Peck Hotel in Fort Peck.

Fort Peck isn’t a Fort (although it was named after one), it was yet another town built to house construction workers – this time for Fort Peck Dam. Fort Peck has several places on the National Historic Register, including the hotel and the amazing wooden art deco Fort Peck Theatre, which when it was built in the 1930s showed movies 24 hours a day and could seat 1200 people. Today it stages pro-am productions on weekends during the summer and has an amazing reputation. I was leaving a day too soon to catch the opening night of Annie.

Fort Peck Dam was another of FDR’s New Deal dams, providing employment for some 10,000 people during the Great Depression. Rather amazingly, it was the subject of the cover photograph on the very first issue of Life magazine.

The hotel had a private function on that night so wasn’t offering dinner. I must have looked disappointed, even more so when it turned out that the nearest eating oppportunities were several miles away: the chef was happy to serve up if I didn’t mind when I ate and chose from a limited menu. I was more than happy to oblige.

Greetings from Kim at the Confluence,

I'm honored to be mentioned in your blog and hope you are having a wonderful and safe journey along the Lewis and Clark trail!

Well hello Kim, was good to chat to you too, and hope your trip to the British Isles comes to fruition.