Another broken night – this time by a thunderstorm that crashed through Sioux City at about 3am. No obvious damage there, but further north plenty of evidence that some serious winds had buffeted trees and overturned rubbish bins. And there was the sad news that 16 campers had died in Arkansas due to flash flooding – a grim reminder that all the various weather warnings were to be taken seriously.

Thus in sombre mood, my first stop of the day was to the Sergeant Floyd Memorial in Sioux City. Charles Floyd was, quite incredibly, the only member of the Corps of Discovery to die on the journey. When one remembers the deprivations the group endured over two winters and crossing the Continental Divide, not to mention numerous encounters with grizzly bears and the less friendly of the local tribes, it is staggering that loss of life was not higher.

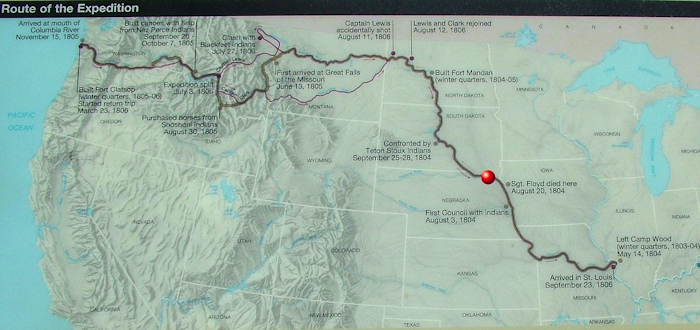

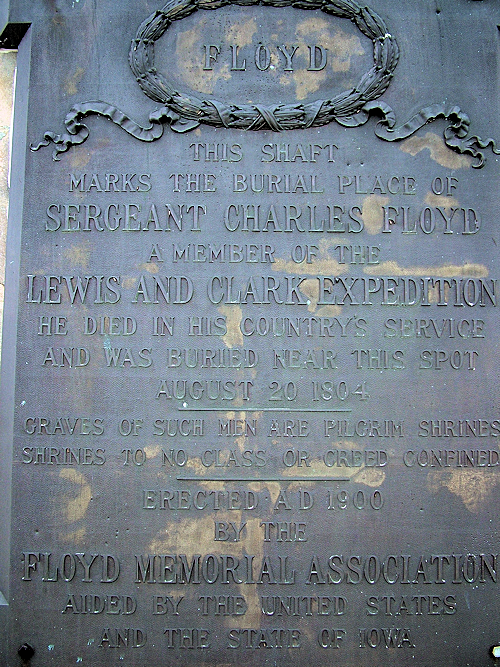

Floyd – one of three sergeants on the trip – fell violently ill on August 19, 1804, just over three months into the expedition. Clark described him “as bad as he can be to live”. The captains diagnosed his affliction as “Beliose chorlick” (bilious colic). Before noon on August 20, the Corps pulled up to the east bank at what is now Sioux City and Floyd passed away. Lewis & Clark had tried everything they knew to save him but to no avail. He was given a full military burial at the highest nearby point. It is now believed that he died of appendicitis, which at the time was fatal. There was nothing that Lewis & Clark could have done. Floyd became the first US soldier to die west of the Mississipi.

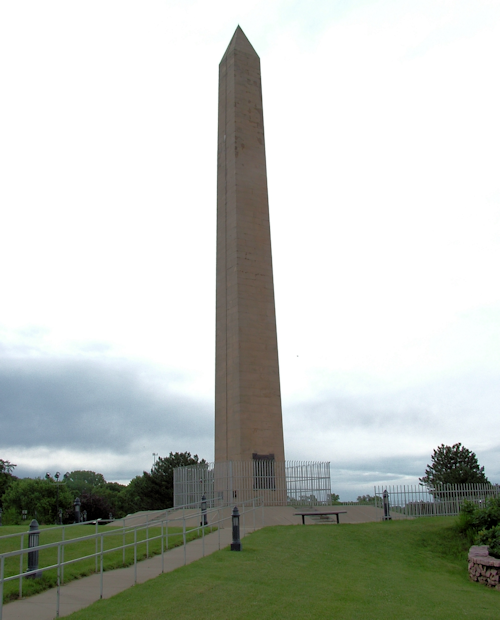

The Floyd Memorial – a cenotaph perched on a bluff – is 110 years old. By 1857 the river had eroded the bluff named in his honour and almost destroyed the grave. His remains were reburied further from the river. In 1894 Floyd’s recently discovered journal was published, which revived interest in him and his remains were transferred to urns and a large marble slab marked the site. A fundraising effort for a permanent monument was begun and the cornerstone of the cenotaph was laid on August 20, 1900, 96 years to the day after he died.

Today the spot overlooks I-29, the Missouri and South Sioux City (the Nebraska part of Sioux City, Iowa).

The day after Floyd’s death, the Corps shot its first buffalo. Unsurprisingly, I had yet to set eyes on one although farmed herds do still exist in the Dakotas, and wild herds in national parks such as Yellowstone. I wasn’t quite in buffalo country yet though. August 22nd saw another “first”, as the Corps voted for a new sergeant to replace Floyd – the first US election west of the Mississippi.

This election took place across the river from Ponca State Park, where evidence of the storm that had ripped through overnight was far more widespread. The roads winding through the forests were littered with large twigs and sticks.

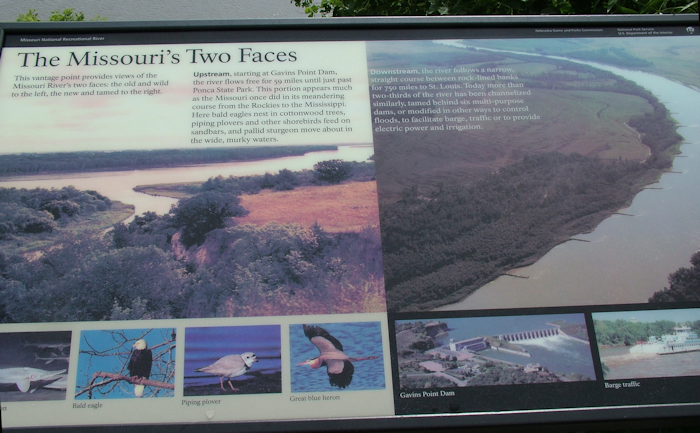

The excellent visitor centre focuses on the ecology and wildlife of the Missouri National Recreational River, as this stretch is known. I was leaving the Lower Missouri behind and entering a section where the river connects a series of dammed lakes from around here right through into Montana. The section downstream from Gavins Point dam (the smallest of the six Missouri dams) to Ponca is one of the very few parts of the whole river that would be – at least in character if not in course – as Lewis & Clark would have found most of the Missouri. Unconstrained by walls or levées, it is a wide, raggedy river; slower moving but exuding a much greater sense of an organic entity shaping the landscape at will.

The view from Three State Overlook almost shows the difference perfectly, but trees on the bluff prevented me from seeing just round the downstream corner to where the river suddenly narrows as it becomes managed. So, they’ve taken a photo for you.

North of Ponca is Spirit Mound Historic Prairie. One of the very few spots where you can be assured of standing exactly where Lewis & Clark would have stood. Or could have been had the path not been completely flooded and impassable.

So I had to make do with photographing one of the very few spots where I could be assured that Lewis & Clark had stood. Not quite the same. Spirit Mound Prairie is now owned by the South Dakota Parks Department and the area around the mound itself has been planted with many native species to recreate as far as possible what Lewis & Clark would have seen. The mound is a “roche moutonée”, shaped but not flattened by the last retreating glacier 13,000 yeras ago.

Lewis & Clark were told that it was the residence of devils:

They are in human form with remarkable large heads and about 18 inches high, they are very watchful and are armed with sharp arrows with which they can kill at a great distance…. So much do the Omaha, Sioux, Oto and other neighboring nations believe this fable that no consideration is sufficient to induce them to approach the hill“. – William Clark

At the end of August, the Corps camped by Calumet Bluff near present day Yankton, SD. Although there is a visitor centre perched on the bluff, any attempt to imagine the view as Lewis & Clark would have seen it is nigh impossible as most of the bluff and surrounding area was blasted away in the late 1940s and 1950s to build Gavins Point Dam and the resulting Lewis & Clark Lake. Nevertheless, the rainclouds lent an air of portent to the spot.

The spot was significant for the expedition as it was their first encounter with the famed Sioux Indians. The Sioux are divided into three main groups: Yankton, Teton and Santee. These were the Yankton Sioux and the meeting went reasonably well. Some of the chiefs agreed to go to Washington although apparently they believed the gifts the Corps had brought them were insufficient. Jefferson had singled out the Sioux as being the most important tribe for Lewis & Clark to bring on side as they controlled the river trade north of here. Later encounters with the Sioux would be less amicable.

The view from the visitor centre is perhaps of more interest for the modern day visitor for the sight of Highway 81. What’s so special about Hwy 81? It’s one section of the Pan-American Highway that runs from Alasaka to the tip of South America (although the designation is unofficial in the United States).