After all the rain, the blue skies of a Tuesday morning in Bismarck were quite the treat. I took the River Road (of course), destination Fort Mandan – an extremely significant location on the Lewis & Clark Trail. I didn’t know about Keelboat Park on the edge of Bismarck. It was home to another replica keelboat and some bizarre statues of who I presume are Lewis, Clark and Sacajawea although there’s no plaque identifying the artist or subjects of this bit of colourful if rather basic sculpture.

A more compelling sculpture stands outside the visitor centre in Washburn, which forms one attraction together with Fort Mandan down the road. The visitor centre is one of the better ones – and also more frequented.

The main exhibition is aimed perhaps slightly more at a younger audience, with lots of “imagine you were negotiating with the Indians” and “what would you have taken on a long journey” sort of questions. But there’s enough for us seasoned L&C visitor centre hands to enjoy too, and an interesting section on the Mandan, Hidasta and Arikara tribes, who ended up all living in this area more or less together before moving north in the wake of the devastating 1837 smallpox epidemic.

Fort Mandan itself is a reconstruction and isn’t even on the actual site of the original fort but that’s par for the course round these parts. And why is it so important? Well, this was where Lewis, Clark and the rest of the men spent their first winter. From November 1804 to April 1805 they hunkered down here against the harsh North Dakota winter.

The dimensions of the reconstruction are accurate, but the historical society that runs it does not know the exact internal layout. I was surprised at how small it was.

There were three rooms for the men, a guards room, the room for the captains, two storage rooms and an all important blacksmiths.

Three important things happened at Fort Mandan. First, it proved to be an excellent place for building team spirit. The rather rag-tag bunch that had assembled some months earlier had all worked hard but some, on occasion, had not lived up to the code the captains expected of them. During this winter they became a well-oiled cohesive military unit. It doesn’t seem that anything special was done to encourage this, but the mutual dependency in tough conditions, and a pervasive sense of purpose certainly helped bond the Corps together, which would be critical in the months that followed their departure from Fort Mandan.

The second thing that happened was that they virtually ran out of food. Unsurprisingly, game is hard to come by in the depths of winter and hunting parties, sometimes including the captains themselves, would be out for several days tracking buffalo and sleeping in the open. But eventually they were forced to trade with locals, especially the Mandan tribe with whom they developed a very close and friendly relationship.

Once the Indians understood that the blacksmith (a craft they had never encountered before) could sharpen their metal implements, they asked if they could have their axe blades sharpened, or even made, in the smithy. This ran contrary to the peaceful mission of Lewis & Clark. The captains explained the problem to the chiefs who apparently said they would take that on board, but would they mind just sharpening the blades anyway, in exchange for food of course. The captains saw they had little choice if they were not to starve and thus the smithy was working overtime and the Corps soon had a surplus of food. Quite what purpose the axe blades were used for history (i.e. the Captains) does not record. A question of don’t ask don’t tell one presumes.

The final thing that happened at Fort Mandan was that Sacajawea joined the story (finally). She was a Shoshone Indian from much further west, who had been captured by the Hidasta and then been given as a wife to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French fur trader who offered his services to the Corps as an interpreter (for local Indian languages, not French, obviously). Only small hitch – he wanted his 16-year-old pregnant wife to come too.

This must have seemed highly irregular, but in my abridged version of the journals it doesn’t even merit a specific mention. Sacajawea of course went down in legend as the native woman who guided Lewis & Clark across the continent. Which isn’t true. What is true is that she was a key part of the expedition, not least when it came to an encounter with the Shoshone much later in the trip. She also saved valuable cargo from being lost in the river and endured everything the rest of the group went through during the awful slog through the mountains. Lewis helped deliver her baby, Jean-Baptiste, during the stay at Fort Mandan, and he too accompanied the expedition. No wonder Hollywood lapped up the story and embellished it every which way.

I rather liked Fort Mandan and it was easy to imagine the men huddled up together around their fireplaces, as local tribespeople came and went with food and goods. There were many late nights of dancing and merriment apparently, all against the backdrop of sub-zero temperatures and thick snow.

The Corps did not move on until April, just one week after the ice had finally melted on the river. One boat was sent back to Washington with some of the specimens Lewis had discovered including magpies, a prairie dog and a sharp-tailed grouse. The rest of the men continued north. I’d picked up my own specimen – roadkill victim number 3 was a small bird that was now lodged in the front grille of the car. Nice. I avoided treading on potential victim number 4 on the nature trail around Fort Mandan.

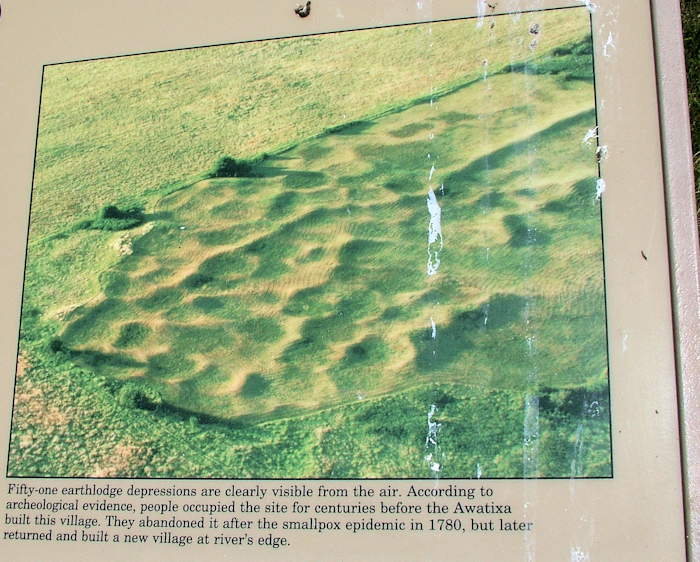

A few miles upstream, north of present day Stanton (with its public fish-cleaning station) is Knife River Indian Villages, a National Park site. There’s not a whole lot to really see here, apart from the visitor centre and a reconstructed earth lodge. It was the site of several large Hidasta villages. There is evidence of Hidasta settlment on this site dating back to the 14th century, and of human activity here going back more than 11,000 years.

What remains today are the indentations left by earthlodges. You only need the slightest of elevations to be able to see the marks in the ground where the original lodges stood. Unfortunately, there’s nowhere to get such elevation, and instead you simply see some bumpy ground.

Only one of the visible villages was around when Lewis & Clark came through, and that was almost certainly where Sacajawea was living. The Hidasta were not especially welcoming to the Corps, partly becasue the Mandan – who wanted the trade monopoly with the Americans – told the Hidasta that the expedition was going to kill them.

In one of the anomalies of time zones, it also happens to be in Mountain Time (GMT-7) – the time zone border cuts through North and South Dakota, although I would be back in Central time again as soon as I crossed the river.

Garrison Dam – the 5th largest earth dam in the world – is some two miles long. Tours of the powerplant are available but need pre-booking so I went to the Fish Hatchery, which breeds vast quantities of all the various fish that populate the lakes. Rather oddly, you are allowed to take a self-guided tour of the hatchery, which is pretty much access all areas. Depending what time of year you go, there’ll be more or less action. There wasn’t a whole lot going on in mid-June, but I did see some fish in some tanks and lots of birds on the nature trail by the lake.

Riverdale, ND doesn’t have many claims to fame. It’s the town on the east side of Garrison Dam and was built entirely to serve the dam construction. When the dam was finished, anyone from the various construction camps who wanted to move permanently to the area was housed in Riverdale, which was run by the federal government until 1986.

It had a high school, which closed a few years ago and has been converted into what might be termed in Europe a “boutique hotel”. It was full, so I wasn’t staying there – I was staying across the road at the very unboutiquey Riverdale Inn. I’d had low expectations, but was very pleasantly surprised – had an apartment to myself for a smidge over $50.

I ate at the school-cum-hotel, which was like sitting in on the pilot of a new comedy drama series. Earl behind the bar huffed and puffed with every new drinks order, locals came and went, some getting slaughtered. A Russian (!) waitress had to ask what almost every drink was (in many cases this was entirely understandable – people were drinking half rose/half red, and someone had a beer topped with tomato juice. I called this a “Bud-dy Mary”, though no doubt it has a proper name). It was a strange although by no means unpleasant evening. If I’m ever in Riverdale again (*splutter) I’ll make sure to book earlier.

From Riverdale I was heading to Fort Peck, but you may have to wait a few days for the story of that and my two upcoming days at Virgelle as I’ll be offline until Saturday.